Feb 9, 2026

High performance in school isn't about working harder—it's about managing your physical, emotional, and mental energy like an athlete manages their training, through cycles of effort and recovery.

Becoming an Academic All-Star - TLDR

Core Idea: High performance isn't about working harder. It's about managing energy like an athlete manages training.

The Problem: Schools focus only on intelligence and willpower. They ignore your body, emotions, and energy systems.

The Solution:

Physical Capacity (Foundation): Sleep, nutrition, movement aren't luxuries. They're performance tools. When your body runs on empty, your brain can't perform.

Emotional Capacity: Stress is inevitable. The key is recovery speed. Learn to downshift your nervous system instead of numbing it with scrolling. Plan recovery in advance.

Mental Capacity: You're training either short-term attention (scrolling) or long-term attention (sustained focus). Academic work is a marathon, not a sprint.

Purpose (Peak): Connect your effort to becoming someone, not just getting grades. Love the challenge, not just the outcome.

The Key Shift: Stop pushing constantly. Start oscillating between effort and recovery. Work in 90-minute cycles with real breaks. Your energy is a muscle that needs to contract AND release.

Real Examples:

Jordan: Added sleep, movement, and breakfast → GPA jumped half a point, studying became 50% more efficient

Alex: Built 15-minute reset rituals after stress → Recovered faster, stopped spiraling

Sam: Trained attention progressively from 15 to 45 minutes → SAT scores up 150 points

Bottom Line: Top performers need to train your whole system, not just your brain.

—

Becoming an Academic Athlete: What High Performing Students Do Differently

It's 11 PM. You're barely finished with the assessment that's due by midnight. Your eyes are scanning the same paragraph for the third time, and nothing is landing. Your phone buzzes. You glance at it, just for a second, and fifteen minutes evaporate into a feed of short videos. When you finally look back at your textbook, the guilt hits harder than the tiredness. Sound familiar?

If there's one thing you're desperately searching for as a high performer, it's the ability to show up when it matters. To think clearly when the pressure mounts. To stay steady when deadlines pile up like cars in a fog. Some students seem to have this figured out. They grow sharper under stress, like a blade on a whetstone. Others, just as talented, start to fray at the edges.

For years, teachers and schools have tried to crack this code. They've handed out planners and taught study techniques. They've talked about growth mindset and grit. And these things help, don't get me wrong. They're treating the symptoms, not the disease.

Here's the thing most educational models get wrong: they treat you like a floating head. As if your performance is purely a matter of what happens between your ears: intelligence, knowledge, memory, maybe a dash of willpower. Recently, we've started talking about mindset and emotional resilience, which is progress. Occasionally someone mentions purpose or motivation.

Almost nobody talks about your body.

And yet your body is the foundation of everything. Think about it: when was the last time you had a brilliant insight while running on four hours of sleep, no breakfast, and two energy drinks? When you perform at your peak, it's not just your brain firing. It's your whole system humming. Physical energy. Emotional equilibrium. Mental clarity. A sense of meaning. When one gear slips, the whole machine starts grinding.

High performance isn't about working harder. It's about managing energy like an athlete manages their training.

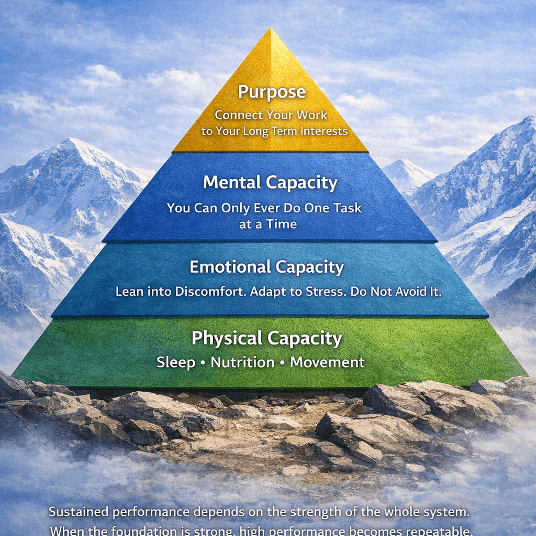

Imagine your performance as a pyramid. At the foundation, you've got physical capacity: sleep, movement, fuel. Without that base, everything wobbles. Above it sits emotional capacity, your ability to bounce back from stress instead of letting it accumulate like sediment. Then comes mental capacity, sustained attention in a world designed to fracture it. At the peak? Purpose. The quiet conviction that this effort is shaping who you're becoming, not just what grade you'll get.

Each layer depends on the one below. Neglect the foundation, and the whole structure becomes fragile. Strengthen the base, and you can handle more weight at the top. This is what separates academic elites from students who simply work hard. They understand they're training a system, not just filling a brain.

The Zone

You know what it's like to be outside the zone. It's sitting down to study and feeling your brain slide off the material like water off wax. It's knowing you should start that assignment and instead finding yourself reorganizing your desk. It's understanding the content perfectly in your room and then blanking the moment the exam paper hits your desk.

The zone feels different. Time just flows. Your attention doesn't wander; it locks in. Challenges don't trigger that sinking feeling; they trigger curiosity. You're not fighting yourself to focus. You're not forcing it. You're just there.

Here's the crucial part: this state isn't a personality trait you either have or don't have. It's not some mystical gift bestowed upon the naturally talented. Academic elites aren't people who never feel anxious or depleted. They're people who know how to find their way back to center. They've trained the skill of recovery.

Think of it this way: your energy isn't a gas tank that slowly empties until you collapse. It's more like a muscle that contracts and releases, contracts and releases. Push it constantly without letting it release, and eventually it cramps. Human beings are oscillatory creatures. We're designed to pulse between effort and rest, stress and recovery, output and renewal.

Most students ignore this rhythm entirely. You treat yourself like a machine that should run at maximum capacity until you crash. And sometimes, it works. Most of the time it doesn't. Concentration gets shallow after school end. Emotions get touchy when you’re tired or hungry. Motivation feels like another color on a mood ring instead of a dial that you can adjust. Procrastination, which you usually call a problem, now becomes your solution.

The goal isn't to eliminate pressure. If you're aiming high, pressure comes with the territory. The goal is to learn how to oscillate: effort, then recovery. Push for a while, then relax. If you learn how to work with your natural 90-minute rhythms, your system stays resilient instead of slowly fraying at the seams.

Physical Capacity: The Foundation

You probably radically underestimate physical energy because academic work feels mental. And here's a fact your brain doesn't want to admit: it's part of your body. When your body runs on empty, your thinking slows down, your attention becomes as reliable as faulty Wi-Fi, and your emotional control goes out the window.

Physical capacity determines your ceiling. It sets the limit for how much mental and emotional work you can handle before your system starts pushing back. When your physical tank is full, mornings start with clarity instead of dread. Your focus holds for more than twenty minutes. After a hard task, you bounce back instead of needing an hour to recover. Stress feels like something you can manage, not something managing you.

When that tank empties? Everything changes. You sit down to study and tiredness hits you like a wave before you've even started. Small tasks feel like boulders and your mind drifts. You start reaching for quick hits of dopamine: social media, snacks, anything, just to feel something other than fog. At night you're wired. During the day you're numb.

This pattern is epidemic during exam seasons. You stretch your hours like taffy to keep up. You decide that sleep is now optional. Your meals become sporadic or skipped entirely. Movement? That's the first thing to go. Meanwhile, you feel wired and tired, edgy and empty, and your body lurches from spike to crash, spike to crash, and here's what makes this dangerous: you misdiagnose physical depletion as a motivation problem. You think, "something is wrong with me" or "I just need to push harder." That's like using every app on your phone when your battery is on 1%. The problem isn't insufficient willpower. It's insufficient fuel.

There are a lot of habits that separate true high-performance athletes from the average person. Olympic athletes don't view rest as weakness. They view it as part of the training cycle. They understand that adaptation happens during recovery, not during the workout itself. Likewise, academic high performers treat sleep, nutrition, and movement as performance tools, not lifestyle luxuries. They understand that physical recovery isn't what you do after you've finished the important work. Physical recovery is what allows tomorrow's work to actually be effective.

There's another principle here that most students ignore: the ultradian rhythm. Your brain operates in roughly ninety-minute cycles of high and low efficiency. After sustained focus, your mental processor starts to overheat. Most students try to power through this natural dip, white-knuckling their way to the end of the hour. What you get is diminishing returns: slower thinking, worse retention, increased frustration, and stronger desires to “do it later.”

Academic all-stars treat that dip as data, not failure. When focus starts to fracture, they pause and step away. They let the system reset, sometimes for just five minutes and then they get back to work. Over time, these micro-recovery breaks make their whole system more efficient.

Consider Jordan, a junior taking three AP classes. When we first met, Jordan's routine looked like this: hit snooze three times, skip breakfast, crash hard around 2 PM, come home exhausted, scroll for an hour "to decompress," then force studying from 7 PM until midnight or later. On weekends, Jordan would sleep until noon trying to catch up, which only made Monday mornings worse. Jordan had been a committed rugby player freshman year but gave it up because “there wasn’t enough time.” The pressure felt unsustainable. His grades were still holding, but only narrowly, and even after quitting, his schedule somehow felt just as full.

The shift started small. Jordan committed to one non-negotiable: sleep by 11 PM on school nights, no exceptions. To make this work, studying had to start earlier, which meant cutting the post-school scroll session from an hour to fifteen minutes, and then the phone went into airplane mode and to another room. Second change: movement. Not a full return to competitive rugby, but something. Jordan started shooting hoops in the driveway for twenty minutes before homework, three times a week. Nothing intense. Just movement and fresh air. Third change: actual breakfast. A banana and peanut butter. Scrambled eggs. Anything besides skipping a meal.

Within three weeks, the changes compounded. Morning energy improved. The afternoon crash softened. Most surprisingly, studying became more efficient. What used to take three hours of distracted grinding now took ninety minutes of focused work. Jordan's spring semester GPA jumped half a point. The anxiety didn't disappear, but it became manageable. Jordan recently told me: "I thought I didn't have time to sleep or exercise. Turns out I didn't have time NOT to." The foundation of the pyramid was holding.

Emotional Capacity

I once worked with two students with the exact same workload, same deadlines, same extracurriculars. One felt constantly behind, perpetually on edge, saying that they feel ‘like they're sprinting on a treadmill that keeps speeding up.’ The other didn’t agree. They said they felt challenged but not crushed. The difference? Emotional capacity.

Let's be clear: emotional capacity isn't about becoming a zen monk who never feels anxiety. If you're doing anything that matters, pressure is part of the deal. The distinction is recovery speed. How quickly can you return to baseline after stress? Academic all-stars aren't stress-proof. They have systems in place to deal with the stress because they know it’s not going away.

When emotional recovery is weak, stress becomes cumulative. One rough class sets the tone for an entire day. One disappointing result becomes a story you tell yourself about your future. One comparison to a classmate triggers hours of spiraling self-doubt. Your nervous system stays activated, stuck in fight-or-flight mode, and concentration becomes nearly impossible.

You face a particularly insidious trap here. Many of your "breaks" don't actually lower stress. They just mask it. Here's how it works: You sit down to study. The material feels pointless, difficult or unclear. Your body tenses slightly with that familiar discomfort. Without thinking, you reach for your phone. Within seconds, you're pulled into a cascade of short videos, messages, notifications. The tension drops as relief floods in. Your brain just learned something powerful: discomfort triggers escape, escape brings relief. This skill is learned and reinforced every single time you feel that wave of relief wash over you. Over time, this creates a feedback loop. The more pressure you feel, the stronger the urge to scroll. The more you scroll, the more work piles up. The more work piles up, the more pressure you feel. Round and round it goes. This isn't laziness. It's conditioning. You've trained yourself to escape discomfort rather than work through it.

The problem is that this kind of relief doesn't actually restore emotional capacity. It distracts you temporarily, sure. Your nervous system stays wired. When you return to the work, that underlying discomfort is still there, often amplified by guilt and lost time.

Top performing athletes understand that the hardest part of any workout is beginning. Once they start, momentum carries them. Similarly, academic elites focus on starting, not finishing. That’s what allows these students to downshift the nervous system deliberately. They don’t need to finish for the sake of finishing. They work in a way that allows them to keep working.

They also understand something counterintuitive: mental recovery matters as much as mental effort. Some of your best problem-solving happens when you step away from the problem. When your brain shifts into a lower-demand state (walking, showering, staring out a window) it reorganizes information in the background. Connections form and solutions surface. This is why the answer to a stubborn question often arrives when you're doing something completely unrelated. Mental performance improves when effort and recovery alternate, not when effort is forced continuously.

Even brief interventions work: a five-minute walk, stepping outside and feeling air on your face, changing rooms, breathing slowly and purposefully. These aren't dramatic interventions. They genuinely bring your system back toward neutral.

The goal isn't to delete your social media or swear off scrolling forever. The goal is to make recovery conscious instead of reflexive. To choose it rather than collapse into it.

Alex, a senior in IB, used to experience what we call "emotional flooding." One bad grade on a chemistry quiz would spiral into a three-hour mental spiral about not getting into college, disappointing parents, having no future. A single critical comment from a teacher would ruin the entire day. While other people seemed to have a dial for their emotions, Alex's nervous system was like a power switch that was either on or off. Sleep and friendships suffered. Alex stopped playing guitar, something that used to bring genuine joy, because "I only want to do things that I’m good at and I’m not very good at that." Everything became high stakes.

Alex's turning point came from an unexpected place: watching post-game interviews with professional MMA fighters. Alex noticed when these athletes lost, even in championship matches, they were disappointed but not destroyed. They processed it, then shifted focus to the next opportunity, they acknowledged that they had worked as hard as they could and took their loss as the next opportunity to improve. They had a recovery ritual: process, move on.

Alex decided to build one. After any stressful event (bad grade, difficult test, argument with a friend), Alex committed to a fifteen-minute reset before doing anything else. Sometimes it was a walk around the block without a phone. Sometimes it was sitting outside watching clouds move. Sometimes it was playing guitar for exactly one song, no pressure to be perfect. The rule was simple: fifteen minutes of genuine recovery before returning to work or making any decisions. Process, move on.

The results weren't immediate, but they were real. Alex started noticing the gap between the stressful event and the emotional reaction. That gap grew. A bad quiz grade still stung, but it didn't derail the next three hours. Alex could feel the stress, acknowledge it, take the fifteen minutes, and then move forward. Emotional capacity was building like a muscle. By graduation, Alex told us: "I used to think stress management meant avoiding stress. Now I know it means recovering from it faster." The second layer of the pyramid was strengthening.

Mental Capacity: Training the Spotlight

Mental capacity is your ability to aim your attention where it needs to go and keep it there. In high-pressure academic environments, attention is your most valuable currency. Many students try to improve performance by logging more hours. Here's the uncomfortable truth: quality of attention matters far more than quantity of time.

Modern life is an attention shredder. Notifications, multiple tabs, constant task-switching. Your mind is comparing your inner life to everyone else's highlight reel, and its doing that at a time when youre just bored enough to be scrolling. Even when you put your phone away, your mind is still processing all of those comparisons.

That’s partly why screentime is irrelevant. If you spend 30 minutes scrolling, you have a very different outcome than someone who spends 30 minutes listening to a podcast. A better indicator of your ability to sustain attention might be how often you check your phone. The average person picks up their phone more than a hundred times a day. That's not building your capacity for deep focus. It's training your brain to expect novelty every few minutes.

Deep concentration starts to feel uncomfortable, almost itchy. You interpret this discomfort as boredom or lack of discipline, when really it's just that your attention has never had the chance to stabilize.

Here's what most people miss: you have a choice. You can practice short-term attention or you can practice long-term attention. To practice short-term attention, simply scroll. Practice that multiple times a day. Check your phone 100+ times every day for years and your brain gets very good at rapidly switching between stimuli, at seeking novelty, at surface-level processing. To practice long-term attention, you have to stick to a task despite not loving it.

Think about marathon runners versus sprinters. Both are elite athletes. Both train intensely. A sprinter's entire race is over in seconds, requiring explosive power and perfect form in a brief window. A marathoner must maintain focus, pacing, and mental toughness for hours. Both skill sets have advantages and disadvantages. In the world of academics, one approach clearly stands out more than the other. Academic work is a marathon, not a sprint. If you've only trained your attention for ten-second bursts, you're going to struggle at mile thirteen.

Academic all-stars treat focus like an athlete treats endurance. They train it deliberately, in intervals. They remove unnecessary noise. They begin each work session with a clear target so their attention has somewhere to point. They understand that focus is a skill that atrophies without practice and strengthens with use.

Sam's attention span had shrunk to almost nothing. A typical study session looked like this: open a tab with the textbook, read two sentences, check another tab. Write three words of an essay, check Instagram. Start a math problem, watch a TikTok. Sam was genuinely trying. The problem was that Sam had spent years training and practicing short-term attention without realizing it. Every time Sam felt even slight discomfort or boredom, the phone provided instant relief. Sam's brain had learned that focus should last about thirty seconds before getting a reward. Anything longer felt unbearable.

When Sam tried to study for the SAT, the reality hit hard. Reading comprehension passages require sustained focus for several minutes at minimum. Math problems require working through multiple steps without distraction. Sam couldn't do it and panic set in. "Maybe its ADHD." That wasn't the issue, but Sam had definitely spent years training the wrong skill.

Sam's solution came from an unexpected conversation with a cross-country runner. The runner explained interval training: you don't build endurance by running marathons on day one. You build it gradually. Run for five minutes without stopping, then seven, then ten. You train the capacity over time; you delay the gratification of relief for longer intervals. Sam decided to apply the same principle to attention.

Week one: study sessions were fifteen minutes of focused work with no phone in the room. Just fifteen minutes with the phone in a different location, not just face-down on the desk. Week two: twenty minutes. Week three: twenty-five minutes. The growth was gradual but measurable. The first few sessions were genuinely hard. Sam's brain screamed for stimulation. Discomfort peaked around minute eight. Sam learned to recognize sustained attention as a skill to build rather than as a matter of genetic willpower.

By week six, Sam could sustain forty-five minutes of genuine focus. SAT practice tests became manageable. Reading passages that once felt impossible now felt challenging but doable. Sam's scores climbed 150 points in two months. More importantly, the skill transferred. Studying for finals became more efficient. Sam reflected: "I thought I had an attention problem. And maybe I do. Either way, I'd been practicing sprints my whole life and then wondered why I couldn't run a marathon." The third layer of the pyramid was locked in.

Purpose Capacity

Physical energy supports effort. Emotional stability supports resilience. Mental focus supports execution. Purpose? Purpose supports persistence.

If you're driven purely by grades, you live on shaky ground. When results are good, confidence soars. When results dip, your sense of identity cracks. Pressure becomes heavier because every outcome feels like a verdict on your worth. Performance becomes a high-wire act without a net.

Elite athletes often say that they love competing more than winning. They love the game itself. It makes no difference that their 'real life' doesn't require the skill set they need for their sport. They don't need to love every grueling hour of practice. A basketball player doesn't shoot free throws for six hours because it's fun. A swimmer doesn't wake up at 4:30 AM for pool practice because they enjoy being cold and tired. They do it because they love the challenge, the growth, the process of becoming better.

Academic all-stars lean into learning because it's hard, not because they know they'll ever use the skills in real life, and certainly not because they like the subject. They don't bother with deciding how much they will or will not need the skills later in life. They understand that the struggle itself is valuable. They connect their work to something deeper than the next report card. Purpose doesn't have to be some grand, Instagram-worthy life mission. It can be quiet and personal. It's the belief that this effort, even when it's hard, even when it's frustrating, is sculpting the person you're becoming.

Students with strong purpose think in terms of growth and capability rather than just outcomes. They see difficult work as training, not torture. They measure success not only by what grade they received but by how they showed up: their engagement, their focus, their grit. They're less rattled by comparison because their scoreboard is internal, not external.

Purpose gives pressure meaning.

I once worked with a student we’ll call Dave. He claimed he couldn't focus in class unless he liked it. This lack of interest in science made focusing impossible. Dave and I decided that he would try to take notes, but not for himself. Instead, his notes would be for students who were absent. When another student got his notes and thanked him, he told me that note-taking wasn't about what he liked or didn't like; it was about helping someone else. When Dave connected the task to a sense of purpose beyond himself, staying on track became effortless. The work didn't change. The meaning did.

Becoming an Academic All-Star

Most high-performing students start their journey the same way: when demands increase, you push harder. And for a while, this works beautifully. Grades stay strong. Momentum builds. Then, gradually or suddenly, pushing harder produces diminishing returns. Energy drains faster than performance climbs. Focus fragments. Stress accumulates. Motivation flickers instead of burns.

The turning point comes when you realize the problem isn't more effort. The problem is the absence of recovery.

Becoming a high-performing student means shifting from a linear model of performance to an oscillating one. Instead of working until you collapse, you learn to pulse between effort and renewal. Instead of relying on motivation to show up, you build routines that protect your energy automatically. Instead of reacting to pressure, you train your system to handle it.

This shift doesn't happen overnight. It's not dramatic. It happens through small, deliberate adjustments that compound over time. You start prioritizing sleep like it's non-negotiable. You take real breaks instead of numbing breaks. You notice when your focus is slipping and step away for five minutes instead of grinding through two ineffective hours. You connect your effort to something that matters to you, not just to someone else's expectations.

Over time, these adjustments accumulate. Focus sharpens and stress becomes more manageable when recovery quickens. Confidence deepens, not the loud, fragile kind that depends on constant external validation, but the quiet, steady kind that comes from knowing you can handle what's in front of you.

The goal isn't to eliminate pressure. High-level academic environments will always be demanding, and unfortunately the world doesn’t stop just because you’re having an off day. The goal is to become someone who can meet those demands repeatedly, perform when it counts, and remain strong enough to keep going.